WARBURTON REFLECTIONS

Looking Back through the Rear View Mirror

I was a remote area teacher in WA in 1970, then again in 1974-75. Both periods were at Warburton Ranges in far eastern WA.

Our remote service in the Northern Territory was from July 1975 until December 1986. Included were appointments to Numbulwar, Angurugu on Groote Eylandt and Nhulunbuy.

I will write a little about my experiences and memories during those periods. Variations in living and working in those places during those years sharply contrast with education in 2021.

OUTBACK EDUCATION IN THE ‘NOT TOO DISTANT PAST

Warburton Ranges (WA) in 1970

In the early 1970s (1970, 1974-75), I taught at Warburton Ranges in WA Laverton, our nearest town over 500 kilometres away. We had no regular mail service. A mail truck came in once every six weeks. Outbound mail went to Kalgoorlie with anybody who happened to be travelling in that direction.

Warburton is 552 kilometres from the small town of Laverton (8.5 hours by road in 2021). Kalgoorlie, the nearest service centre, is 892 kilometres (close to 12 hours in 2021) away. In the 1970s, with the road to Laverton from Warburton largely unmaintained and, in essence, a ‘track’, that leg of the trip took far longer.

There were no phones, minimal radio reception, or connection with the outside world besides VJY radio.

VJY radio was controlled by the Mission (1970) and the Department of Health (1974). This mode of communication is not private, not even for telegram transmission. Everything was public.

In 1970, the United Aborigines Mission (UAM), which administered Warburton, had a generally sturdy and reliable truck, an Atkinson, which ran a shuttle supply and mail service between Warburton to Kalgoorlie and return. In clear and still conditions, the dust raised by the Atkinson could be spotted. Children and people would begin to look anxiously west when the trucks were due. A high point on the track was a ‘jump up’ at about 40 kilometres from Warburton.

Children would start to get excited, with that excitement rising to a crescendo when the truck hove into view after crossing Elder Creek four kilometres to the west of the town. It would pull up in the town centre, opposite the store, its yellow paintwork and tarpaulin-covered load covered in outback track redness and dripping with fine dust.

The mailbag, for us all, was a point of excitement. The bag or bags entered the superintendent’s large, sparsely furnished home. He opened the bags and distributed letters and parcels to designated points of the room for staff. Mail for the indigenous community went into a section for later sorting and distribution to recipients through the store-cum-office.

At that time, the emphasis was on letters because the era was pre-facsimile and pre-other forms of electronic transmission. Salaries were dispatched by cheque. Teachers and other government workers would receive three and sometimes four pay cheques at a time. Understandably, we had accounts at the store for the purchase of foodstuffs and other goods.

On the return trip to Kalgoorlie via the Atkinson, outbound mail went via the mailbag. However, trips were not always predictable. The truck was often off the road for lengthy periods because of the need for repairs. The truck was sturdy, but the track to Laverton was one massive stretch of uncertainly, including hundreds of kilometres of punishing corrugations.

This meant piggybacking on the goodwill of travellers and those passing through Warburton to accept and post mail for those looking to communicate with the outside world.

Apart from teaching, I was a student undertaking a correspondence course to upgrade my teaching qualifications. At one point in time, I sent an exam paper to Perth via a pilot who sometimes came to Warburton. He posted the exam paper at the Perth Airport, but it was never received. I was offered two options.

I could either forego a second examination or be given a pass mark because my coursework average for assignments completed was at a distinction level. Or I could resit another examination. I elected a ‘pass’ level for the course.

The mission generated the power supply at Warburton in 1970. They had a diesel-powered generator. The power plant was operational for only a few hours each day. From Monday to Friday, power was supplied between 5.00 pm and 10.00 pm from Monday to Saturday. On Sunday, the power was shut down at 9.00 pm. (These limited hours of supply may have had to do with diesel costs and the fact that funding for the overall operation of Warburton largely depended on donations made to the mission from private sources.)

Although we had a gas stove, each cylinder of gas purchased cost a whole week’s salary, so the use of gas had to be very strictly limited. Washing, cooking and other domestic and work-related functions dependent upon power had to take place during those limited hours. An electric frypan was useful.

From an educational and schooling point of view, activities in 1970 had to be conducted without recourse to electricity. This meant that heating in winter and cooling in summer were not options available to teaching staff. Our school building was of aluminium construction with masonite lining. With its three classrooms linked by an enclosed walkway, the building was suffocatingly and fetidly hot in summer and often desperately cold in winter.

When we returned in 1974, the school had its power generator and no longer had to rely solely on the community. That made things so much better. Some of the locals who had cars also appreciated that engine generating our power. When the sump oil was drained from the engine, it would be claimed and used to top up the oil levels in some of the vehicles.

A vast remoteness about the landscape leading to and from Warburton left those passing through feeling outback majesty.

Characteristics and Climate

The area around Warburton Ranges was semi-desert scrubland and Spinifex. However, every vestige of vegetation had vanished from the country to the north, south, east and west of the settlement, to a distance of at least 4 to 5 km. And the fact that Warburton sat in the middle of a veritable dustbowl meant that every time a breeze would blow up, the settlement would be shrouded in dust.

Sometimes we only had a light dusting (with zephyr-like breezes), but on many occasions, with strong easterly winds, dust filled every nook and crevice of our school and houses. Keeping things clean was a never-ending task.

We didn’t have school cleaners, so our task as a small group of teaching staff was to look after our homes and the school when it came to basic cleaning. The windows in the school and our houses were of the louvred variety; keeping dust out by shutting those windows was impossible. A carpet of red on desk and table tops, chairs, cupboards and other fittings was constant.

On one occasion, we had a visitor who was to be a house guest. On arrival, she immediately set to spruce the house (obviously thinking we had no interest or capability in household cleanliness). The wind came up and blew unceasingly for a period – and she came to understand why the house (also aluminium with masonite wall lining) was as it had presented on her arrival. When the job was done, there was a brief time for any celebration.

Winter winds were dusty, cold and bitter. From April to the end of August, overnight temperatures in the low, single digits were common. Daytime temperatures were often no more than 15 to 18 degrees Celsius, often accompanied by bitter westerly winds. At recess and lunchtime, children would sit along the length of the eastern school wall (the lee wall), soaking up sunshine that was not impacted by wind.

Trying to convince the WA Education Department of the need for fuel-fired heaters for schools and homes was impossible. After all, we only lived 32 kilometres south of the Tropic of Capricorn, so how could we POSSIBLY be cold?

The seasons of the year at Warburton were seasons of contrast. In summer and winter, the sun rose early and set early. Our geographic position meant that the community would have been better served by adherence to central standard time rather than the Western standard time.

Summer temperatures ranged between lows, averaging 22 degrees (C) to 38 degrees (C). In winter, the temperature range was between 6 degrees (C) to 21 degrees (C).

Temperatures during shoulder months ranged between these extremes. Averaging does not tell the whole story because there were times when it was much hotter and much colder than recorded averages.

One of the exciting phenomena of winter months was a vista of “black frost “, which covered large areas in the pre-dawn. Some cattle troughs around Warburton had been used for cattle in earlier times. Those troughs were invariably frozen over, often for some hours each day during the dry and cold mid-winter months.

Warburton’s annual average rainfall was; however, there was a good deal of fluctuation in just how those faults occurred. In 1970 we had only 19 points of rain for the whole year—just a few millimetres. I remember to this day, children running, romping and playing on the strip of green lawn adjacent to the school in sheer delight as those points of moisture fell from the heavens.

When we went back to Warburton in 1974 – 75, there was a real deluge. Elder Creek burst its banks, and the mission was flooded. Water drained away from central Australia, including the Warburton area, and finished cutting channels through to the Great Australian Bight. Warburton, which didn’t have a shred of green anywhere around 1970, became part of the hinterland in which incredible growth and green was everywhere. The vagaries of nature and impossibility of prediction, helped make the community a place of unpredictability.

I kept a diary for the more significant part of my professional life. This is a habit that continued into my retirement years. A few years are missing in the late 1970s and early 1980’s but I have records otherwise. I kept copies of letters duplicated and sent to friends and relatives and have various other documents. (However, from 1982 onward, I kept a diary. Some contain more detail than others, but the value of keeping a journal for all sorts of professional and personal recall needs cannot be overstated. My Father always kept a diary, and it is to him I owe thanks for this becoming, for the most part, an ingrained personal behaviour.)

The First Day of my Teaching Career

My first diary was in 1970. It was a foolscap size diary with a page allocated to each day, and the first day of my full-time teaching experience turned out to be pupil free by accident rather than design. It was a day, now over half a century old, I will never forget.

Warburton Ranges School Headmaster Bruce Goldthorp, an educator with seven or eight years of teaching experience, was on his first day in the role of headmaster. A kerfuffle with beginnings outside the schoolyard quickly entered the school precinct as he lined the students up. One of the older students (1) had told another that her Father had snakes in his legs. Her Father had obvious and prominent varicose veins in his legs. This ‘observation’ was part of an altercation that had occurred sometime prior between the two students.

This comment was relayed to her Father, who took umbrage at the deep insult. She took off into the school and up the classroom connecting passage, being chased by the offended Father and family. With his weapons to hand, he and his family came into the schoolyard, seeking retribution on the utterer of that comment.

The girl’s family, who had commented, became alerted to the dispute and began chasing after the offended family with appropriate weaponry (no firearms were involved).

The result of this situation was a scatter of all students, first as spectators to the event, which rapidly moved from the schoolyard into the community, thence into the distance. There was no school that day: Our first school day of 1970 at Warburton was the second day of the school year.

(1) Names and identities withheld.

Finding the Way – A Process of Discovery

Beyond the school day, life at Warburton in 1970 had a good deal to offer. There was always something going on in the community, and the dynamics between staff could be interesting. There was a strong mission element, with some non-mission staff connected with education and some aspects of welfare. I used to attend some of the religious functions organised by mission staff, for this was the only way of really keeping abreast of trends about what was happening within the community.

The Warburton Store was basic in terms of the goods available for sale. Our diet was strictly limited, with tinned food (including meat, fruit and vegetables) providing a staple diet. PMU Braised Steak and Onions were my absolute favourites. Forest fruit and vegetables were rare. Flour, sugar and tea were staples. The store had a bakehouse connected, with bread being a significant element of the local diet.

The locals would buy bread and put it up on posts or other structures out of the reach of dogs. When it dried to quite bone-hard proportions, they would break it into pieces, dip it in billy tea and eat it in the moistened state.

Tea and sugar were purchased in made-up lots. It was customary to place the whole amount of tea and sugar into a billy can of boiling water and drink it (or use it to soak bread) until the container was close to empty. The billy can then be filled with water and reboiled. This process was repeated until the tea and sugar flavour was depleted.

Fresh meat was a rarity, and management somewhat unusual and possibly bizarre. Periodically, mission management would organise a group that would go into the Warburton hinterland, select a cow from among what was a semi-wild herd, kill it, dress it and bring it back to the store on the tray of a utility.

The beast was then taken into the store and hung in a section that was semi-dark and serviced by a hanging hook attached to a solid beam. Beneath the beasts was a wooden floor, made somewhat slippery by congealed blood dripping onto it over time.

People wanting meat were given a sharp knife and invited to cut off portions they desired. This method of self-service had limited appeal. Although the area was secluded and not as hot as the general surroundings, the meat went off quickly. This butchery method became less practised over time. Locals paid for goods from the proceeds of welfare checks cashed at the store. Staff ran accounts on credit, paying them down when pay cheques arrived.

Fuelling Convoy Cars

In 1970, there was little traffic on the ‘Outback Highway’ from Laverton to Ayers Rock (Now Uluru). Four-wheel drive was almost (but not quite) mandatory for intrepid travellers. High wheelbase 4WD primarily constructed vehicles that could negotiate rugged outback terrain were standard for a tour offering company, “Outback Australia”.

Occasionally, a convoy of vehicles would play “follow the leader “from Perth to Alice Springs. The lead vehicle was generally well equipped, but people coming behind in ordinary conventional cars would have had some difficulty on many track sections.

I’m sure they helped each other when the need arose, although some confronting difficulties were left to rectify their problems there catch up with the rest.

There were often 15 to 20 vehicles in the convoys. They needed to pull in at Warburton for fuel. The store dispensed petrol using an ancient fuel bowser, which allowed the pumping up of five or six gallons of fuel at a time from the concrete underground storage tank. Pumping the fuel up from an underground tank was done by way of a hand-operated lever. When the bowser bowl was full, the fuel was then siphoned by hose from the bowl into the fuel tank of the motor vehicle.

Whenever these infrequent convoys came into town, they would generally arrive in the late afternoon when the school day was over. I would head over and volunteer to pump the fuel and have conversations with persons whose vehicles were being filled.

When fuelled, vehicles would be driven into a second line developed for those ready to continue the eastern journey. On one occasion, a car with a male driver and three female passengers was in the second line. The vehicle, a large tourer (possibly VW), had a large perspex roof. Nearby, some boys were kicking an old and worn football to each other. One of the kickers sent the ball in a high and misdirected fashion into the air. The ball came down, not in the arms of one of the other players, but square onto the Perspex roof of the tourer. The roof smashed with large and small fragments, and the football landed among the three waiting ladies.

It became a case of losing a roof and gaining a football – for the boys bolted before the three women became fully aware of what had happened.

One thing was for sure. The next several hundred kilometres of the trip would have been very dusty indeed!

In those days, the airstrip was a smoothed-out dirt strip periodically maintained just east of the settlement. Fuel for planes was ferried down on a needs basis on the back of a utility or truck and then hand pumped into plane fuel tanks by pumping from 44-gallon (120 litres) drums containing aviation fuel. Fuel was kept under surveillance as much as possible because of substance abuse issues and the cost per drum to freight the fuel (usually on the Atkinson).

The Ballet Company

On one occasion in 1970, a twin-engine plane, from memory, a twin-engine Cessna 412, flew into Warburton. On this occasion, the pilot and passengers, after landing, did not leave the plane and walk up to the community, a distance of several hundred metres. Instead, the election was to taxi the aircraft off the strip, up an incline (not the steepest but quite apparent), coming as close as manoeuvring allowed to the settlement buildings.

It turned out that the passengers were ballet company members on the way from Perth to Alice Springs. They were attired in a way that revealed their individuality as persons connected with the expressive arts profession. The locals were amazed, indeed gobsmacked by the revelations of these personages as they alighted from the plane. Their dress and gait held unique appeal. The local young men could not match these visitors for apparel, but they took them off perfectly for the way in which they deported themselves while out of the plane and on the ground. The mimicking was accurate and entertaining. It lasted for a long time after the plane was returned to the airstrip, fuelled and taken off to continue its journey.

Warburton in 1970 was quite an isolated place. But we could always expect the unexpected, and visitors turning up out of the blue was part of what made the unexpected a part of community life.

A Focus on Vehicles

Vehicles were very much part and parcel of the Warburton Ranges scene. Once purchased and returned to Warburton, most did not last a particularly long time. They were driven and driven until they could be driven no more.

The Outback Road (then much more of a track) was dotted with abandoned vehicles dumped and left adjacent to the road. Some were burnt out, most stripped of parts, but all were left to weather in the heat of summer and the cold of winter months. Some, in fact many, did not make it back to Warburton or, if being driven from Warburton to other destinations, did not complete their journeys.

I remember the Docker River Truck. It was bought with money that had been part of a settlement by Western Mining with a local elder when he sold his promising chrysoprase mine to the company.

The mine was about five kilometres from Warburton, just off the track to the east of the settlement. The Docker Truck, a brand new two-ton vehicle, was so named because it made several trips from Warburton to Docker and back after purchase.

This was before we arrived at Warburton in 1970. By then, the truck, undrivable and beyond economic repair, was outside the southern fence of the school. It had resisted just over 3,000 miles on the odometer. The value of vehicles, once purchased, depreciated immediately. The lives of most were very short.

There was an exception to this rule. Someone bought a yellow Holden FJ sedan. It went and went and went and went! It had an unstoppable motor, notwithstanding that oil used to top up the engine was generally second-hand lubricant that had been drained from elsewhere. The engine mounting wore out from fatigue and from travel over bone-shattering tracks and terrain. So the engine was held in place by green, forked sticks cut from trees that grew at some distance from Warburton.

The vehicle changed hands at regular intervals and, each time, sold for more than the price for which the vendor had purchased it. The Holden defied all odds and just kept on going.

Obviously, it had an endpoint in practical life, but what a vehicle it was. It went far, far further than the distance ever travelled by the Docker Truck. It also offered a quite everlasting memory that shows what can happen when odds and averages are challenged.

The Social Context of Life

In 1970, housing in and around Warburton was somewhat creative but without structure or substance. Indigenous Australians did not live in the township for whom the settlement had been provided. They lived in camps to the north, east, south and west of the community. They were roughly divided on the basis of family and clan boundaries, taking into account compatibilities and incompatibilities. Avoidance requirements were taken into account, but as the settlement was central to all, tensions manifested themselves from time to time.

Sometimes conflicts were minor, confined to an exchange of language. On other occasions, the competition was more intense, involving physical interaction. Traditional weapons were sometimes used, and spearing, usually for payback purposes, was uncommon. Some of these were ritualised. Generally, the health clinic attended and looked after anyone suffering injury medically.

There were no houses, the camps being the construction of wiltjas, made of tin, hessian and other scrap materials. They provided shade but very little else. The structures were blisteringly hot during summer and frigidly cold during winter, when campfires to offer warmth became all-important. Many of these structures had corrugated iron sheets used to build a barrier around the dwelling. These sheets of metal afforded some shelter from the wind.

Blankets were used to help create warmth, and people also slept next to their dogs for added warmth. Locally, cold nights were referred to as ‘two dog nights’, ‘three dog nights’, and so on, indicating just how cruel and shiveringc were those nightly conditions.

There was no housing for Indigenous people other than three units on the west side of the settlement. As people had become deceased either in or nearby, these houses had been effectively abandoned. Some people lived in old cars and vehicles that were no longer running.

Community homes for staff were a mixed collection. One or two places were quite decently constructed, but most buildings for occupational purposes or living were elementary.

Some houses were constructed of local rock, with walls held in place by locally made mud matrix. Education houses were of aluminium with some metal lining.

Warburton Ranges was established as a mission in 1932, Warburton Ranges. At that time, Warburton Mission was under the management of the United Aborigines Mission (UAM), with the mission’s operational headquarters in Melbourne. The UAM represented several earnest Christian religions, including Baptists, Pentecostals and other dedicated Protestant groups.

I am drawing on several online sources to elaborate a little further.

“The United Aborigines Mission ran residential institutions for the care, education and conversion to Christianity of Aboriginal children, mainly on Mission stations and in children’s Homes. The institutional care provided by the UAM was closely tied to Government funding and policy in Indigenous affairs.

The United Aborigines Mission (UAM) (also known as UAM Ministries, United Aborigines’ Mission (Australia), and United Aborigines’ Mission of Australia was one of the largest missions in Australia, having dozens of missionaries and stations, and covering West Australia, New South Wales and South Australia in the 1900s. It was first established in New South Wales in 1895.”

“The UAM ran residential institutions for the care, education and conversion to Christianity of Aboriginal children, mostly on mission stations or in children’s homes. It was mentioned in the Bringing Them Home Report (1997) as an institution that housed Indigenous children forcibly removed from their families”

“The United Aborigines Mission (UAM) was established in Western Australia in 1929 as a successor to the Australian Aborigines’ Mission (AAM). The UAM ran a number of missions and hostels around Western Australia. In October 2019, Sharrock Pitman Legal Pty Ltd, a legal firm based in Melbourne, advised the Find & Connect web resource that the United Aborigines Mission and UAM Ministries were in the process of being wound up. As of February 2020, UAM Ministries remained a registered charity, last reporting to the Australian Charities and Not for Profit Commission in September 2019.” Sources from online Wikipedia

(While completing a Post Graduate Diploma in Intercultural Studies through Mount Lawley College of Advanced Education in 1976, I researched some background on Warburton Ranges and wrote a dissertation titled. “The evolution of cross-cultural relationships that developed in the Warburton Ranges Area in the period 1873 to 1935, taking into account factors that contributed to the comparability or fragmentation of relationships, to determine whether the Aboriginal Cultural Identity was strengthened or weakened because of contact with Europeans in Socio-Economic and Spiritual context.”

I would be happy to share this dissertation with anyone who might be interested. My email address is henry.gray7@icloud.com Feel free to make contact should you so wish.)

Our first period at Warburton coincided with the last years of mission control before the Government took over responsibilities from mission days. During the time we were at Warburton in 1970, the mission was still a mission. That status was designated on signage identifying the settlement to those coming into the town by road from the west.

Spiritual Matters

A building constructed of rock walls with a galvanised roof stood as a church in Warburton. We never witnessed it being fully utilised as a place of worship, but in earlier years, indications are that church attendance was very regular. Indeed, in the early mission days, the story was that unless people attended worship, they might not be given the supplies they needed.

My understanding of worship in 1970 was that spiritual matters were faithfully attended by a small group of dedicated Indigenous people, mostly women. Some within this group worked closely with the two mission linguists working on translating the Bible into Ngaanyatjarra. This was an extensive and detailed task, made more so because of the complexities of translation.

I recall on one occasion that the linguists tried for months to equate the dimensions of Noah’s Ark into some understandable form for the sale of recognition. None of the hills were suitable to allow the accuracy of measurement. There was an open depression in the nearby country named ‘Biel’. The difficulty was one of the conceptual challenges. How could a three-dimensional object (Noah’s Ark) be equated to an elongated hole in the ground (Biel)? In concept terms, slipping the ark into a gap did not work.

At Easter in 1970, a band of Salvation Army musicians came to Warburton to share their music. An evangelist, the Reverend Jack Goodluck came with them. The Reverend set up a HUGE painted screen in the middle of the large cleared area in the settlement centre.

The screen depicted a man with a load of sin on his back. He stood at a crossroads not all that far from the top right corner of the painting. Heaven was right up in that corner at the end of a short ‘road’.

Most of the painting was devoted to the highway south to hell and damnation. The painted scenes of hell, fire, brimstone and oblivion were horrific. Goodluck preached to the large painted screen. Young people, particularly, were terrified by what was going to happen if they did not get good. On the following school day (Tuesday after Easter), many children came to school declaring they were not sinners but rather amongst the saved. They had each been given pledge cards attesting to their determination to make it to Heaven, cards which they had signed as an affirmation of their future direction in life. There are ways and ways of encouraging change in people. This method had a fairly short life when it came to long-lasting influence.

Educational Essence

Some of the children we taught were young people with great potential. Sadly (as will be shown in a later segment), the expectations held for Indigenous children in WA (and elsewhere) were, in the 1970s (and following years), well below par. At that time, awareness of the world outside Warburton was strictly limited because these were the days prior to modern communication technologies available in 2021. Outback transceivers and receivers through VJY two-way radio were the only communication open with the outside world. And in 1970, there was only one such unit at Warburton, controlled by the mission-managed hospital.

In those days, the school year was divided into three terms: two weeks’ holiday at the end of term one (May) and term two (September). There were eight weeks of holiday at the end of each school year.

During the 1970 May school holidays, we drove out from Warburton to Perth, then up to Moora (our home town in WA about 150 kilometres north of Perth) before returning to Warburton via Kalgoorlie, Leonora and Laverton. This was quite a lengthy round trip in our Holden EH Utility. In those days, there were no seat belts or a limit of three people to the bench seat of a utility or any other vehicle.

To offer them an appreciation of the wider world and to broaden their horizons, we took two students out with us for the holiday period. Pamela Brown was a daughter of a senior Pitjantjatjara Elder who had four wives and quite several children. Helen Ward was a keen young student who, like Pamela, always did her best at school. We thought these girls would benefit from an opportunity to experience life beyond Warburton.

These girls were exemplary in terms of their conduct and behaviour (including their ability to acclimatise and adjust to the various situations confronted) during our time away from Warburton during that holiday period. It was tough to judge just how the wider world impacted the two girls, but I would vouchsafe that their learning was significant and that they had much to relay back to their family and those at Warburton on their return. In the years to come, Helen Ward became a respected educator filling a significant role in schools that were set up within the Ngaanyatjarra cohort of schools.

The Scourge of Petrol Sniffing

Negative influences of European/Caucasian culture had a habit of impacting Indigenous communities, and Warburton Mission was not immune to these temptations. One of the most harmful and humanity-weakening habits to creep into remote missions and communities was that of petrol sniffing.

Sadly, the scourge of sniffing is decades old, and the outcomes are still the same as in the 1970s and 1980s. Research undertaken by the Menzies School of Health in Darwin illustrates some aspects of this chronically psychologically addictive habit.

“Petrol sniffing has been a significant source of illness, death and social dysfunction in Indigenous communities over the past few decades. Sniffers start to experience euphoria, relaxation, numbness and weightlessness but often end up with severe and irreversible brain and organ damage.

The part of the brain that controls movement and balance is damaged, and eventually, users cannot walk or talk properly. Many sniffers end up in a wheelchair with severe, long-term brain damage.

Sniffing also leads to behavioural and social problems, and sniffers often get into trouble with the law for vandalism, violence, robbery and sexual assault. They find it difficult to stay at school and hold down jobs.

Poverty, boredom, unemployment, and feelings of hopelessness and despair have contributed to the problem, aided by the low cost and ready availability of petrol.

However, with the introduction of the federal Petrol Sniffing Prevention Program, including the rollout of Opal Fuel, and the NT Volatile Solvent Abuse Prevention Legislation, significant reductions in petrol sniffing in remote communities have been observed.” Source: Menzies School of Health Online Site 2021

While written decades beyond our time at Warburton, the Menzies text explains key elements of this chronic affliction.

In 1970, petrol sniffing was new to Warburton. Its ‘novelty’ impact on the behaviour of children who tried sniffing, causing them to laugh, stagger and act drunk, caused parents and adults to laugh at displayed behaviour. Concerned community members tried to dissuade the core of users from stealing and sniffing petrol fumes from the small tins into which it was siphoned but with limited success.

When we left Warburton at the end of 1970, the problem was not community-wide, with the group being relatively small. But the habit and the number of users were to grow, as we discovered when returning to Warburton in 1974.

The Critical Role Played by Relationships

In my first year as a teacher, 1970 was somewhat of a steep learning experience. I learned much and hopefully gave back as a classroom teacher and community member during the year (which is very fully dealt with in the first diary I ever kept). Most of my years through the 1970s and 1980s were spent in Aboriginal (these days ‘Indigenous’) education. The desire to continue teaching and education in an indigenous context must have been born.

As a ‘newby’ teacher (albeit a mature aged one who had left a family farm to train as a teacher) I learned a great deal during our twelve months at Warburton. In educational terms and for many reasons, I learned a lot about what to do by learning a lot about what not to do. These lessons derived from personal experience helped me separate good teaching practices from ones that were less effective.

The lessons learned were also based on observation of what others did and how they dealt with particular circumstances. I would also add that my training as a teacher (a two-year course in those days) was of great help when it came to translating and applying that training in practical teaching situations.

And treating Aboriginal adults and children as equals in regard and conversation helped. While the Warburton of 1970 was unique and different, the people were people, and we were all on the same plane together. I tried to keep it that way in conversation.

When some people went into communities to live and work, it seemed they tried to ingratiate themselves with the local people to learn about Aboriginal culture and ceremonies. Undue inquisitiveness, I believed to be unwise.

A respectful interest was a far better option, and waiting to earn the confidence of people so they shared was a superior approach to developing cross-cultural relationships.

It was also essential to represent one’s social and cultural mores appropriately. Working in a remote community did not mean abrogating one’s own background in order to embrace that of others. It was quite possible to be symbiotic in terms of both groups living and associating together in the same area. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people had – and have – much they could share, including learning and teaching, in a context of proximity and association.

Warburton in 1970 was a different and unique experience, one that helped when it came to preparing me for teaching beyond my first year.

OUTBACK EDUCATION IN THE ‘NOT TOO DISTANT PAST

Warburton Ranges (WA) in 1974-75

When we left Warburton after our year in 1970, I assumed that was the end of our association with the community. I was keen to take on the challenges of a one-teacher school, partly because of their uniqueness and because my training has encompassed preparation for teaching in these situations. Within reason, the WA Department of Education tried to accommodate those teaching for a year at Warburton with a school of their choice.

So it was that the years 1971 to 1973 inclusive were spent at Gillingarra, a one-teacher school some 40 kilometres south of Moora. It was during these years we had our children. I do not intend to write of educational experiences in a way that goes beyond and into our private lives as a family but to confine writing to matters that relate primarily to education and associated living experiences.

Gillingarra, a one-teacher school, had an average of between 19 and 22 students during my three years. I may well write about this school and my experiences in the future.

Reflection and Warburton Return

Toward the end of our three years at Gillingarra, I began to think about my professional future and where it might be appropriate to look beyond our three years (enjoyable teaching years) in this small community. For some reason, the idea of a return to Warburton had some appeal. When it came time to apply for a transfer (with an eye on transferring to a promotional position), I applied for the position of Headmaster at Warburton Ranges. My wife would be a teacher at the school, and we would have our children with us, should I be successful.

I was appointed to the position, and we began thinking about our return with effect from the beginning of the 1974 school year. Toward the end of 1973, I had the opportunity to visit Warburton for a day, travelling on a charter flight that was going up and back on the same day. That would mean a very early start and a very late return on the chosen day.

So it was that on December 18 1973, I returned for a flying visit to Warburton. This was during the last week of the school year at Warburton, and the Department had given me dispensation to make the trip. That was the prelude to our 1974 return and our second appointment to the community.

A New (Second) Beginning

The beginning of the 1974 school year was ‘back in Warburton’ but for me, in a different context to our previous sojourn. We had a staff of four, with the classroom configuration being the same as in 1970. The primary school block contained three classrooms and a demountable adjacent to the main school building. The main house, into which we moved, was attached to the end of the classroom block, with our ‘old’ house standing opposite that dwelling and separated by a strip of lawn.

Opening the school and lining children up to enter their classrooms brought back memories of day one in 1970. Fortunately, on this occasion, there was nothing like the disruption that had happened four years earlier.

During the time between our two appointments to Warburton, a good few teachers had come and gone. We were the first educators and non-missionaries to return.

While there was still a mission influence at Warburton, there had been a good deal of secularisation of staff at the settlement. In 1970, the Welfare Officer had been an ex-missionary. This was no longer the case. The hospital had been taken over more formally by the Health Department, as had the store.

As Prime Minister from 1972 until 1975, Gough Whitlam and his Government oversaw significant changes. A change in the Australian Government, with the arrival of Labour to the governing benches after 23 years in opposition, led to a shift in how remote Aboriginal communities were regarded. Self-management and self-determination were strategies introduced for remote communities by the new look government.

The following extract illustrates change and is added because it offers background to changes at Warburton. It is drawn from an article by Jenny Hocking and published in the Australian Journal of Public Administration on December 7, 2018.

“Gough Whitlam’s Labor government came to office in December 1972 with a vast and transformative reform agenda, at the heart of which was a fundamental policy shift in Aboriginal affairs away from assimilation and toward self-determination, described by Whitlam as; ‘Aboriginal communities deciding the pace and nature of their future development as significant components within a diverse Australia’.

Whitlam’s commitment to self-determination reflected the United Nation’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which refers to the right of all peoples to ‘freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development’. Whitlam made it clear that Aboriginal Affairs would be a priority of his Government by establishing the first separate Ministry for Aboriginal Affairs and introducing a suite of path-breaking policies for Aboriginal people. Pat Dodson, the inaugural chairperson of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, later described the change in policy and intent under Whitlam as ’a transforming sentiment in this country for Aboriginal people’. This article explores the key features of Whitlam’s Indigenous policy and argues that Whitlam’s commitment to self-determination was a unique and radical policy reframing in Indigenous affairs not seen before or since. These advances were1 wound back by the conservative Government of Malcolm Fraser, and the ‘transforming sentiment’ soon reverted to one of ‘self-management’ and unarticulated assimilation.” Excerpt from ‘A transforming sentiment in this country: The Whitlam Government and Indigenous Self-determination.’

This article explores the key features of Whitlam’s Indigenous policy and argues that Whitlam’s commitment to self-determination was a unique and radical policy reframing in Indigenous affairs not seen before or since. The inaugural chairperson of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation later described the change in policy and intent under Whitlam as ’a transforming sentiment in this country for Aboriginal people’. These advances were1 wound back by the conservative Government of Malcolm Fraser, and the ‘transforming sentiment’ soon reverted to one of ‘self-management’ and unarticulated assimilation.” Excerpt from ‘A transforming sentiment in this country: The Whitlam Government and Indigenous Self-determination.’

Our return to Warburton was predicated by these changes.

Fast Forwarding Warburton – From 1970 to 1974

There were significant changes to the way Warburton operated in 1974 compared to 1971. An incorporated office had been established to run the administrative business of the community. This included an office and banking facilities which had (1970) been managed through the mission store.

The store was under community control, with Warburton being managed by a large consultancy group, WD Scott and Associates, headquartered in Perth. A community adviser appointed by Scotts was the person on the ground who was technically responsible for the day-to-day management of the community.

Mail connections with the outside world were still irregular. There was no regular mail service, especially for outbound mail, as there was no standard air service from Kalgoorlie to Warburton. VJY (still controlled by Health Department) was still the only way of communicating- by transceiver/receiver, with all communications being public to those tuned in at particular times. Charter planes bringing government personnel into the community were not infrequent, but they had no fixed schedule. For this reason, the preferred method of contact from WD Scott’s head office in Perth with the community adviser was a cassette tape.

The Community Welfare Department was represented by an officer who was not affiliated with the mission. He was responsible for over-sighting Warburton, the Ngaanyatjarra area and a pretty large section of the Pitjantjatjara Lands, reaching northeast to Giles and east toward the Blackstone and Peterman Ranges. The community also had a liaison with Docker River just over the border in the Northern Territory.

From a school viewpoint, we had our own generator, which powered our school and the residences. This was particularly handy on the home front because the gas price was still astronomical, a cylinder of gas costing the better part of a week’s wage. We had no air conditioning and no heating capacity for the dry, cold winter months. The community was also serviced by a bigger generator which ran far more uninterruptedly than had been the case four years earlier. It had been relocated to a point just beyond the immediate community.

Three out of four new and quite elaborate (by outback standards) homes had been built on the southern aspect of the community. These were for some of the staff employed under the application of revamped management. The locals lived as they had in 1970. Nothing had changed in that regard.

The Scourge of Petrol Sniffing

On our return to Warburton, one of the saddest changes confronted was how petrol sniffing had become ingrained among the younger set. Petrol sniffing had become a scourge, one making increasing impacts among boys and young men. Boys had quite ingenious ways of relieving vehicles of petrol, siphoning petrol into cans for sniffing. At that time, unleaded petrol and the revelation of opal fuel was well into the future, with leaded petrol being the most used of fuels for vehicles.

One of our support staff members and a firm supporter of our school, Bernard Newberry, worked unceasingly with young people to help them realise the dangers of sniffing. This included everything from an earnest conversation (in which I also participated) to chasing young people who had cans of petrol to tip the evil liquid onto the ground.

The effects of prolonged addiction to petrol sniffing were apparent when we returned to Warburton in 1974. In 1970, I had a young man in my middle primary class who was, in my opinion, quite intellectually enriched. He was experimenting with petrol sniffing during that year. I had hoped he might desist, but sadly, that was not the case. Instead, he became hopelessly addicted to the extent of reducing himself in the intervening three years to a person who had become an empty, vacuous shell.

Our Welfare Officer, Ron Jarvis, was deeply concerned about sniffing, and we organised an outdoor lesson on the subject that he would conduct. He made a model of the body’s vital internal organs using polystyrene, including the liver, lungs, heart, digestive organs and brain. These he connected with wire and hung them into a frame. He explained to children that petrol had a way of destroying people from the inside. He touched the base of a lung with the equivalent of a teaspoonful of petrol. Immediately, the polystyrene lung began to collapse and ‘melt’ dripping onto the ground.

The impact of the petrol spread, melting ‘organs’ with increasing speed, with the brain the last to disappear. This was a graphic lesson with Mr Jarvis offering appropriate comments as internal organs dissipated. The address had some impact, but for the whole of our remaining time at Warburton, we were confronted with the challenge of petrol sniffing

That challenge was one we never gave up trying to surmount. At that stage, we didn’t know that in years to come, volatile substance abuse would continue, with the addition of hard, addictive drugs and substances with the potential to engulf more and more people.

Focus on Hygiene

While educators, we were very concerned about the general health and welfare of the children at Warburton. To that end, we engaged with the children in several ways to try and enhance general well-being issues. From the beginning of the 1974 school year, we decided to encourage children to shower in the community ablutions blocks as they came from their camps each morning. The showers, a community facility, were rarely used, mainly because the only showering option was cold water. In 1974, the galvanised female and male blocks were separated by partitioning and were entirely private.

The ablutions block had donkey boilers attached, but these had to be serviced.

Donkey boilers were 44-gallon (120-litre) drums hooked up with water inlets and outlets as befitting traditional wood-burning bath heaters. In order to facilitate the showering program, I used to go down each morning and light fires under the boilers. The community supplied wood, and I did the rest.

We supervised the showering programs, supplying detergent for each child. Towels were communal and supplied clean each morning by the Health Department staff. After use, they were collected, washed, dried, and readied for the next day.

This service was provided for most of the 1974 school year from Mondays to Fridays.

We oversaw some other aspects of health care for children. From time to time, we organised haircuts for students to assist with health care. We also arranged for children suffering from weeping ears and scabies to go to the health clinic for treatment. Weeping ears were often accentuated and made worse because the condition attracted flies. Dead flies were often found in children’s ears at the health centre. On one occasion, nine flies were removed from one ear and eleven from the other ear of an afflicted child.

These conditions were worse after weekends and holidays because staff kept a regular and supportive check on students during the school week.

The Education Department supplied vitamin and mineral-enriched biscuits for students. They were a small supplement we added to their diet, distributing them at school. Cartons of canned Carnation milk were sent to be made up and distributed at school.

A midday meal and afternoon tea were supplied to children by the community, this being part of the Government funded support program – as had been the case when we first went to Warburton in 1970.

Afternoon tea was a sandwich and a piece of fruit. On many occasions, this food was passed over by children to others within the community who were not provided for by the program.

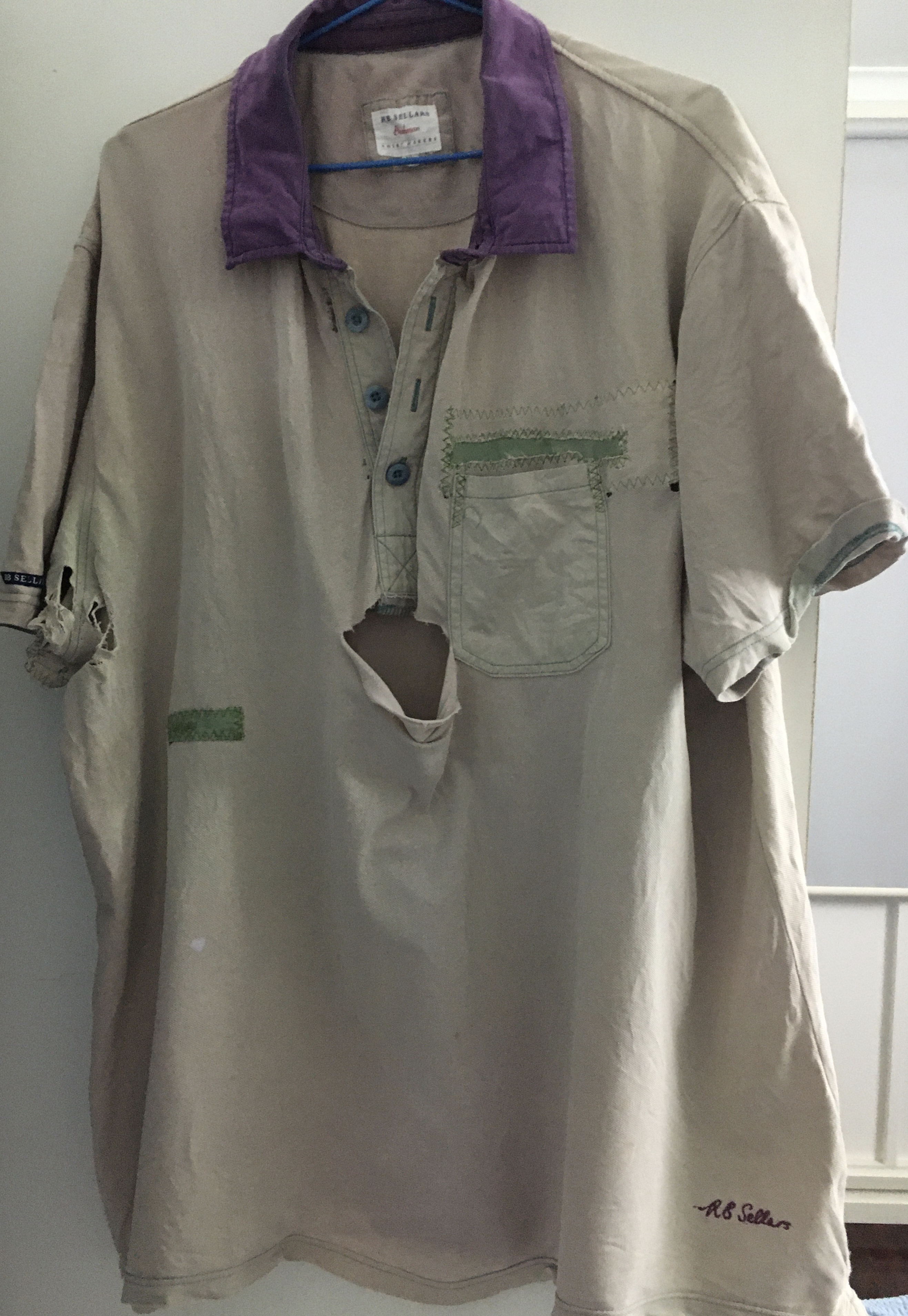

Donated Clothing made a BIG Difference

Helping with personal hygiene and cleanliness was not aided by the fact that members of the Warburton Community, adults and children alike, were not overly endowed with clothing. The scarcity of apparel was not helped, for children at least, because if jumpers and outer garments were removed when it was hot, they were generally dropped on the ground and left behind. While others, in time, might pick up and utilise discarded garments, they tended to be left where they fell.

While clothing, in terms of warmth offered, was not an issue in the hot summer months with their generally warm nights, winter offered a different scenario. The cold wind whipped into Warburton from the dry hinterland, adding very cool days and cold nights.

With the issue of need in mind, and considering that little clothing was carried for purchase in the store, I wrote a couple of letters to newspapers, appealing for clothing donations. The situation was carefully explained. We asked that people consider donating clothes for both adults and children. Clothing donations were to be sent to us via the Thomas Nationwide Transport (TNT) depot in Kalgoorlie. TNT’s period contractor who serviced the Warburton run, Dennis Meaker, had generously volunteered to transport clothing to us freight free from Kalgoorlie. Depending on circumstances, Dennis made the Warburton run each week or each fortnight.

We received substantial donations of clothing. As boxes of clothing arrived, we sorted them into four groups for temporary storage. The divisions were women, men, girls and boys.

On Saturday mornings each fortnight or three weeks (depending on supply), we organised clothing into four areas in the three classrooms in the primary school building. Girls’ and women’s clothes went into one room, with boys’ and men’s in the other classrooms. We organised entry and exit at each end of the passage. As people left with their choice of clothing, we asked for a donation of 20 cents for each item. This money was generally forthcoming, but the clothing was freely given if payment was impossible.

Money collected went into school funds and was used to purchase goods for student use. The amount of money allocated by the Education Department for school requisites was paltry (only a few hundred dollars for the school each year), so this money was a helpful supplement.

Additional clothing stocks meant we could upgrade our care program for students. The showering program outlined earlier was limited because children had to put dirty clothes back on after showering. In that context, children were always in clothes needing a wash.

With second-hand clothing now available, we were able to modify the program. Children showered each morning and put their used clothes back on. When they arrived at school, they changed from these clothes to a second set of clean clothes in their desks. This was done with the appropriate circumspection. After changing, the children then washed their dirty clothes with soap or detergent before rinsing them out. Clothes were then placed in proper drying places within the environment of the schoolyard.

Warburton’s moisture-free atmosphere no matter what season, meant that the clothes quickly dried. Children would then collect and fold clothes, leaving them in their desks for changing the following day. In terms of weekends, Friday’s washed clothes were there for Monday morning.

There were some disruptions to this program; circumstances occasioned these, but it was generally maintained. I like to think it made a difference in the well-being of our students. Importantly, it showed them and their families that we cared.

Self Worth and Personal Pride

We supported students in other ways that promoted a sense of self-worth and personal pride. Senior girls were offered personal grooming opportunities through hair care. They would wash their own heads or those of peers, then take pride in combing and other aspects of hair care. The essential equipment we had for these programs meant that students had to make do in rudimentary circumstances. There were far more plusses than minuses for these extension opportunities, particularly for our older children.

While these activities were supplementary to core education, they needed to be met to provide children with the feeling of well-being that is so important if learning is to be meaningful. We were keen to do the best we could, as a school staff, by the students entrusted to us for educational care and development.

School Attendance

Truancy and non-attendance at school was a key issue. This notwithstanding the support programs in place, which included meals in the community children’s dining room. The problem of school attendance was particularly challenging during the cold winter months. Winter winds were often bitterly cold, sweeping across the flats toward the camps and settlement. With overnight temperatures often around the freezing point mark and not getting above the high teens or very low 20s during the day, one could understand the reluctance of children to move from camp areas to the settlement for the start of the school day.

We often experienced the phenomena of black frost, a sheen of dark hue colour, on the land in the early morning. There was no moisture, but the ground was bitterly cold. The mirage lifted off after the sun rose in the sky, but its disappearance was often slow.

Although we had a clothing program that supported the children, footwear was not a part of what was offered. Children and adults at Warburton were, in the majority, always barefooted.

The cold often made children’s and adults’ hardened feet crack open during winter. Medication to heal cracked feet took a long time to work. I admired how people, despite fractured skin, managed to move around quite adroitly and nimbly. That must have taken courage and fortitude.

One of our Aboriginal support staff members Bernard Newbury (who later became a senior called Warburton), worked hard to convince students about the value of school and education.

Occasionally, I would go out in our Mini Moke into some camping areas to talk with students and parents about school attendance. This contact helped, but the truancy issue was always one offering challenge. I could relate several incidents of a somewhat humorous nature that occurred during times spent encouraging students toward school attendance; however, this chapter is not the appropriate forum for recounting these incidents.

We worked hard to make the school relevant to meeting children’s educational and developmental needs. Basic learning needs (literacy and numeracy) were the focus of learning. “Learning by doing” and “hands-on” experiences were developed in order to help make learning live. Some of these strategies are outlined in the following segment.

In the overall context, I felt that we did a very good job in terms of developing the programs we offered our student cohort so they met curriculum requirements and the needs of students.

The Focus of Learning

In order to afford the best opportunities possible to our student cohort, we planned and programmed in a way that developed logical and sequenced learning. Students learning engagement was also a priority, adding a dimension to what might otherwise have been a chalk-and-talk approach.

We followed the WA Education Department curriculum requirements but considered the need to adjust content to recognise children’s learning to date. There were learning shortfalls that resulted from sporadic school attendance, and we worked to make up for gaps in learning by revisiting subject areas where students needed remediation.

To familiarise senior students with community contexts, we developed a wall and ceiling dictionary organised in an A-Z manner. This was an exercise with a daily time commitment. Students drew a picture of the object, person or subject on a large sheet of cartridge paper. The name or title of the picture was then added, with that dictionary/ identity sheet being added to the dictionary. All wall space was eventually covered.

When writing, students who wanted spelling assistance relating to items covered by the dictionary could check the walls and ceiling until they found what they were seeking. This added to both student independence and confidence when they were writing.

Creative and imaginative writing was a focus. I found that older students, both female and male, greatly enjoyed producing written text. On occasion, children were given pictures and photographs to incorporate as illustrations into stories. Correct spelling of words was encouraged.

There was a focus on handwriting, including the ‘three p’s’ of pencil/pen hold, paper position and posture.

Maths, as far as possible, was situational, with examples supporting operations drawn from local experience and the environment of Warburton and its surroundings.

Children were encouraged to read orally and also to develop skills of understanding and comprehension of the written word.

I kept records of student progress in key learning areas (long, long before the concept of KLA’s was formalised), and we understood how well children were doing. While the interest in school by adults was somewhat remote, we offered anecdotal comments and feedback, but in the social context of informal discussion.

Practical and focused learning opportunities were offered. For instance, the use of and understanding of money was aided by the setting up of a pretend shop with goods for sale. Goods (empty cans, packets and so on) were provided, and money was used. An understanding of adding, subtraction and money management ways an outcome of this program.

There was a focus on both art and drama to reinforce other learning areas, particularly literature.

Doing the best we could for the betterment of students was uppermost in our minds. As will be revealed later, this motivation was not one that met with the approval of educational authorities.

Extending Education

We had some exciting and meaningful times at Warburton, which included extension programs aimed at strengthening and enriching student experiences. One of the most memorable was an overnight camp we organised at a location out of Warburton. This involved taking food for several meals and planning with the community for children to spend the night away from their home camps. The interaction between students and their relaxed manner with each other was a highlight of the brief time we spent in that outdoor situation.

Disproving Relationship Myths

Years later, I reflected on the limitations usually adhered to in terms of relationships, which had not manifested themselves in any way during that time. Neither were these relationship elements pronounced in classroom contexts.

There are two other commonly held belief points that I felt, from personal interactions with students, were little more than myths. The first was that individual children did not like praise for work well done because they preferred to be identified as group members rather than in a singular context. Children often worked in groups, and collective appreciation was an element of recognition. However, I never found individual students reluctant to accept praise.

The other enjoinder offered was not to ask children to look you in the eye, because that was shameful for them. They preferred looking down or away when talking, averting facial contact. Sometimes our predispositions to accepting particular and somewhat opposing viewpoints can minimise our effectiveness as educators in working to develop personality traits and characteristics in children. I found that not to be the case at Warburton and in association with Aboriginal children in other locations.

Swimming and water experience opportunities were limited by the dry nature of the country in which we were living. There was a windmill about 2 kilometres to the east of Warburton, which pumped everlastingly into a 15,000-litre tank. Occasionally, I would take a class of students on a walk to the mill. They would climb into the talk and have a great time in this makeshift swimming pool. The more daring group would climb to the top of the frame supporting the mill, then jump off, ‘bomb shelling’ into the tank. (Imagine the trouble one would be in these days if such an activity was undertaken.) there were no accidents or injuries for children who seemed to have an uncanny sense of safety and self-preservation.

A most memorable swimming excursion was to a waterhole we heard of, located several kilometres southwest of Warburton. We had a new mini-make at the beginning of 1974, which we had shipped to Warburton on the TNT transport. Rainfall had created the waterhole. I loaded 19 (yes, nineteen) young people on the Moke and at a plodding speed, we set out for the waterhole. Occasionally, road conditions made transport impossible, so students would help the Moke through the short intervals of challenging terrain. We made it there and back with the children having a great time in the water. (Once more, you would not be game to undertake such an outing these days for fear of offending OH and S regulations.)

Interdepartmental Connections

One of the programs we were about to establish at Warburton was regular interdepartmental meetings. This enabled health, welfare and education to come together with local community representatives so we could share information and plan together. These meetings helped with the development of understanding between us all. An outcome of these meetings was greater understanding and cooperation between us all.

It often seemed to me that if interdepartmental cooperation existed at higher levels within our respective organisations, the benefit would accrue to the system. It appeared that our superiors, within our respective organisations, acted without recourse to other connected agencies. Reduplication and misunderstanding resulting from a lack of shared focus were a result.

Film Nights

One of the things we could do for the community was organise periodic film nights. We sourced most of our films from the Shell Travelling Film Library and drew on movies available through the Education Department.

A nice patch of green lawn was established on the western side of the main school building. An outdoor projection screen had been permanently constructed, enabling projection from one of our classrooms through an open window once the louvres were removed. We had quite an ancient Bell and Howell projector, giving the locals many hours of film entertainment during 1974 and 75. Shell films were never the latest release movies, but the fact that the company made them available meant they provided us with a valuable service. Films were transported to and from Warburton courtesy of Dennis Meaker, the TNT driver.

On winter nights, audience members would turn up with blankets in order to keep warm. There was no need for this consideration during the summer months.

It was essential to stay with the projector the whole time it was operated. Teachers used every to take turns filling the role of the projectionist. On one occasion, the projectionist decided the projector could do the job automatically. Unfortunately, the spool receiving the viewed film was bent inward. Rather than the film rewinding normally, it quickly started to wind through the projector and onto the floor. At the end of the reel, when the projectionist returned, there were many, many hundreds of metres of film lying on the floor. After several hours, we eventually got it sorted by working the movie like a skein of wool up and down the long passageway connecting classrooms and, from there, bringing it back onto the spool. Never again was the projector left alone.

However, that dilemma did not stop the audience from enjoying the film.

One night, a staff member decided on a private film showing for himself. That was fine. The projector was set up in the classroom nearest our house, where a breezeway separated the classroom and ours. Our children and we needed rest. The projector, with its audio support, droned on into the night. It was getting later, and it seemed the watcher was going to make an all-night marathon of the viewing.

Enough is enough! I jumped out of bed, entered the school building, opened the switchboard and pulled the fuse. The projector stopped dead, and you could hear the teacher (who will remain nameless but the same person responsible for the film spillage problem from earlier) begin to panic.

The following day I restored the fuse, and the problem was solved. The panic lasted for the rest of what was left of the night. That was the last time we had an all-night movie marathon.

Thoughts about Visitors

We used to have many visitors come into Warburton connected with education and other government departments. Often visits were fleeting, lasting several hours at most.

Planes would come in during the morning and be gone by mid-afternoon. There were occasions when people would come in and stay for longer.

Very rarely would anyone visiting bring their own food or food supplies. They expected to be catered for and must have imagined that meal ingredients came out of thin air. John Sherwood and Ed Brumby from Mount Lawley College of Advanced Education, who came to evaluate students completing teaching practice, were the exceptions.

During our second period at Warburton, we were looked after by a butcher in Kalgoorlie. We had a rotational arrangement for food supplies, again supported by the indefatigable Dennis Meaker, who drove the TNT truck supplying Warburton with goods. We had several large eskies in which the butcher sent goods, including meat, frozen vegetables and ice cream. When he arrived, Dennis would drop the eskies at our place. All the goods were unloaded into our freezer. We would then return the eskies with Dennis to the butcher with an envelope listing preferred goods and a blank, signed cheque. This the butcher would fill in after getting our next order together.

Thanks to the goodwill of the butcher and Mr Meaker, the system worked wonderfully well. It gave our family a good supply of decent, nutritious quality feed. And it was from this ‘larder’ that many meals were provided to visitors. I would pay tribute to my wife, who did a massive amount with limited facilities for meal preparation. Much cooking was done in an electric fry pan for, as I have pointed out, the cost of gas made using the gas cooktop and oven far too expensive.

There were no food outlets or takeaway facilities available in Warburton. I make that point because very, VERY infrequently, anyone contributed ingredients or offered to reimburse meal costs. On one occasion, several contractors in town asked my wife if she would cook an evening meal for them. She agreed and was paid for her work.

Most meals were ‘freebies’, which cost us, but allowed those consuming our hospitality to keep their incidental travelling allowances intact.

It Never Rains, But …

We had some exciting and varied life experiences at Warburton Ranges during the course of our terms of appointment. Some had to do with people, others with the environment.

One thing for sure was that no two days were ever the same. And some periods of time were more environmentally challenging than others.

There had been little rain at Warburton during our time there in 1970. In 1974, the story was somewhat different. An abundance of rain fell through to the community and in all directions, north, east, west and south, at one point during the year. The rain was soaking, the ground becoming saturated.

Elder Creek came in from the north and swung west around the community at some kilometres from the community. It overflowed to the north, with floodwaters coming into and inundating a good half of the settlement. Fortunately, our school and houses were in part, remaining dry. The floodwaters only stayed for a day or so before retreating. However, the saturated soil burst into green, with vegetation and plants coming to life. Growth was quick, and the green hue surrounding the community offered what was all too rare visual attractiveness,

Further out from Warburton, trees and shrubs burst forth with new and vibrant greenness. Spinifex, the predominant ground ‘grass’ in the Warburton, Peterman and Blackstone areas, grew with a prolificness that was totally transforming of the species.

The Coming of Mice

Animal life was renewed; part of that renewal brought forth a plague of mice which quickly overran the community. The mice bred prolifically and got into everything. Clothing in drawers and foodstuffs in cupboards fell victim to these vile rodents’ feeding caprices and nesting habits.

Mouse traps were at a premium. I came up with three single spring traps and one with four holes inviting mice to tasty cheese used to bait the traps. Outside our house yard and up against the fence was a 44-gallon drum we used for incinerating rubbish. During the day, whenever we came home (from adjacent classrooms) and at night (as the traps went off to signal more victims), I would take the traps and release the now-dead mice into the drum. We caught a huge number of mice during the weeks of the plague. The most disposed of in any one night was 64. I was up and down all night long.

The mice were into everything. Plastic lids on tins of food formula did not protect the contents of the containers.

Mice would chew through the plastic covers, fall into the food, gorge themselves and then die because there was no escape from the prisons they created for themselves. It was reminiscent of a last hearty meal before execution.

The mice would scurry across our bedding during the night. They could be heard scrambling between the outer wall and Masonite material that doubled as wall lining. They could be heard in the ceiling cavities.

Fortunately, the plague did not last for too long. However, the mice were indeed active while the plague lasted.

Reflections on Warburton Management

There were pros and con’s to how Warburton had been managed in mission days. With the coming of the Whitlam Labor Government in 1972, there were changes mooted for community evolution, and this was across the board. Impacts were Australia-wide. Central to the change was a determination that communities should enter the era of self-determination and self-management. (This was discussed in an earlier section of my writing.)

The intentions were good, but the practices associated with this new approach did not work well for many communities. Readiness for taking on responsibilities requires education, and this was not provided for people in many communities. Many communities took on Caucasian staff to fulfil management functions, too many of these people being ‘found’ by advisory firms appointed to oversee the evolution of community management. Aboriginal people living in communities were often the meat in the sandwich.

Warburton Ranges suffered because of some of these changes. European staff were often poorly prepared to take on management functions. It seemed that some accepted appointments for reasons associated with the need to be away from everyday mainstream life. For some, their moves concerned failed relationships or threatening social situations.

Canine Essence

Others were seeking to escape from unfortunate social habits, including drinking and gambling. While not specifying any particular traits or habits impacting staff at Warburton, it was common knowledge that these were situations that motivated some people to remote area service around Australia.

One of the issues was that people appointed to communities were too often not educated toward understanding the specifics of those places and the characteristics of people living therein. To this end, I offer a compliment to the WA Education Department. As I was going back in 1974 as the school principal, the Department supported me in undertaking a two-week program at the Bentley Institute of Technology to facilitate my understanding of the local language, Ngaanyatjarra. One of Warburton’s long-term linguists, Dorothy Hackett, facilitated the course. Aspects of this program touched, albeit briefly, on social and cultural aspects of living and working in the Aboriginal community of Warburton.

With the passing of time, familiarisation programs were developed with greater or lesser success. With the above background in mind, I will return to elements more focussed the remained of our time at Warburton.

Dogs were very much an integral part of life at Warburton. There were few families without dogs, often in multiples. The dogs were thin, and underfed, and many were riddled with disease. Heartworm was prevalent, the telltale signs being the loss of condition, depletion of energy, dull coats, hair falling out and skin taking on permanent scaliness. Eventually, the dogs would collapse and die. Very sick dogs were often attacked by other canines, the object being to kill and eat them. Similarly, dead dogs were carcasses to be attacked and consumed by dogs remaining alive.

Hunger drove dogs to extraordinary lengths as they tried to sustain themselves. Rubbish bins 44 gallon (120 litre) drums were jumped into by dogs looking for morsels of food to eat. Before burning accumulated rubbish in the bins, it was often necessary to shoo dogs away. I witnessed dogs who happened across unopened cans of food work those cans over with their teeth until a hole gouged in the can revealed the contents. The dog would suck at the punctured tin until its contents were empty.

At one stage in 1970, an artist, Mrs Souness, the mother of our headmaster’s wife, visited Warburton. She did a series of sketches of life around Warburton, including her take on the impact of dogs. She gave me a set of her drawings which I have preserved to this day and would be happy to share by copying for others. Appropriate credits would apply. Her sketches and depictions were very true to life and showed just how dogs interacted with children and adults at Warburton.

Night-time temperatures often hovered in the single digits area on the thermometer during the cold winter months. Windchill exacerbated coldness. People huddled in camps often with minimal blankets and around meagre campfires, used their dogs to create body warmth as humans and canines huddled together. Common parlance described the environmental conditions as anywhere between ‘two dog’ to ‘six dog’ nights. The colder the night, the higher the aggregate assigned to dogs to describe the level of cold.

The value placed on dogs meant that none were ever destroyed. Neither was there any veterinary attention given to these animals. The dogs were prolific breeders because neutering was not practised. Young pups quickly became ill because of heartworm and lived with their lives with this and other afflictions. They took their chances of survival in a world as harsh as any in which dogs have ever been asked to survive. They were a key and integral element of the community’s social fabric. While many dogs may have been inclined toward viscousness, this behaviour was dampened by their sickness and consequent lack of energy.

Pre-service Teacher Education

There has always been a need for teacher training programs to consider those who might be thinking of teaching in remote community situations. The importance of this was (and is) in part to disavow those considering remote teaching of false and fanciful notions based more on romantic misunderstanding than practical reality. First impressions of remote communities are not always lasting, especially for those who visit briefly and then return to full-time occupation after a cursory first glance.

As a person who worked in remote communities in both WA and later the NT as both a teacher and principal, I can say quite unequivocally that preservice teaching in remote communities is best predicated by offering exposure to communities during training years.